SAN JOSE, Costa Rica (AP) вҖ” Violeta Chamorro, an unassuming homemaker who was thrust into politics by her husbandвҖҷs assassination and stunned the world by ousting the ruling Sandinista party in presidential elections and ending вҖҷs civil war, has died, her family said in a statement on Saturday. She was 95.

The countryвҖҷs first female president, known as DoГұa Violeta to both supporters and detractors, she presided over the Central American nationвҖҷs uneasy transition to peace after nearly a decade of conflict between the Sandinista government of and U.S.-backed Contra rebels.

At nearly seven years, ChamorroвҖҷs was the longest single term ever served by a democratically elected Nicaraguan leader, and when it was over she handed over the presidential sash to an elected civilian successor вҖ” a relative rarity for a country with a long history of strongman rule, revolution and deep political polarization.

Chamorro died in San Jose, Costa Rica, according to the familyвҖҷs statement shared by her son, Carlos Fernando Chamorro, on X.

вҖңDoГұa Violeta died peacefully, surrounded by the affection and love of her children and those who had provided her with extraordinary care, and now she finds herself in the peace of the Lord,вҖқ the statement said.

A religious ceremony was being planned in San Jose. Her remains will be held in Costa Rica вҖңuntil Nicaragua returns to being a Republic,вҖқ the statement said.

In more recent years, the family had been driven into exile in like hundreds of thousands of other Nicaraguans fleeing the repression of Ortega.

Violeta Chamorro's , Cristiana Chamorro, was held under house arrest for months in Nicaragua and then convicted of money laundering and other charges as Ortega moved to clear the field of challengers as he sought reelection.

The Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation closed its operations in Nicaragua in January 2021, as thousands of nongovernmental organizations have been forced to do since because Ortega has worked to silence any critical voices. It had provided training for journalists, helped finance journalistic outlets and defended freedom of expression.

HusbandвҖҷs assassination

Born Violeta Barrios Torres on Oct. 18, 1929, in the southwestern city of Rivas, Chamorro had little by way of preparation for the public eye. The eldest daughter of a landowning family, she was sent to U.S. finishing schools.

After her fatherвҖҷs death in 1948, she returned to the family home and married Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, who soon became editor and publisher of the family newspaper, La Prensa, following his own fatherвҖҷs death.

He penned editorials denouncing the abuses of the regime of Gen. Anastasio Somoza, whose family had ruled Nicaragua for four decades, and was gunned down on a Managua street in January 1978. The killing, widely believed to have been ordered by Somoza, galvanized the opposition and fueled the popular revolt led by OrtegaвҖҷs Sandinista National Liberation Front that toppled the dictator in July 1979.

Chamorro herself acknowledged that she had little ambition beyond raising her four children before her husbandвҖҷs assassination. She said she was in Miami shopping for a wedding dress for one of her daughters when she heard the news.

Still, Chamorro took over publishing La Prensa and also became a member of the junta that replaced Somoza. She quit just nine months later as the Sandinistas exerted their dominance and built a socialist government aligned with Cuba and the Soviet Union and at odds with the United States amid the Cold War.

La Prensa became a leading voice of opposition to the Sandinistas and the focus of regular harassment by government supporters who accused the paper of being part of WashingtonвҖҷs efforts вҖ” along with U.S.-financed rebels, dubbed вҖңContrasвҖқ by the Sandinistas for their counterrevolutionary fight вҖ” to undermine the leftist regime.

Chamorro later recounted bitter memories of what she considered the SandinistasвҖҷ betrayal of her husbandвҖҷs democratic goals and her own faith in the anti-Somoza revolution.

вҖңIвҖҷm not praising SomozaвҖҷs government. It was horrible. But the threats that IвҖҷve had from the Sandinistas вҖ” I never thought they would repay me in that way,вҖқ she said.

вҖҳPeace and progressвҖҷ

Chamorro saw her own family divided by the countryвҖҷs politics. Son Pedro Joaquin became a leader of the Contras, and daughter Cristiana worked as an editor at La Prensa. But another son, Carlos Fernando, and ChamorroвҖҷs eldest daughter, Claudia, were militant Sandinistas.

By 1990 Nicaragua was in tatters. The economy was in shambles thanks to a U.S. trade embargo, Sandinista mismanagement and war. Some 30,000 people had died in the fighting between the Contras and Sandinistas.

When a coalition of 14 opposition parties nominated an initially reluctant Chamorro as their candidate in the presidential election called for February that year, few gave her much chance against the Sandinista incumbent, Ortega. Even after months of campaigning, she stumbled over speeches and made baffling blunders. Suffering from osteoporosis, a disease that weakens the bones, she broke her knee in a household fall and spent much of the campaign in a wheelchair.

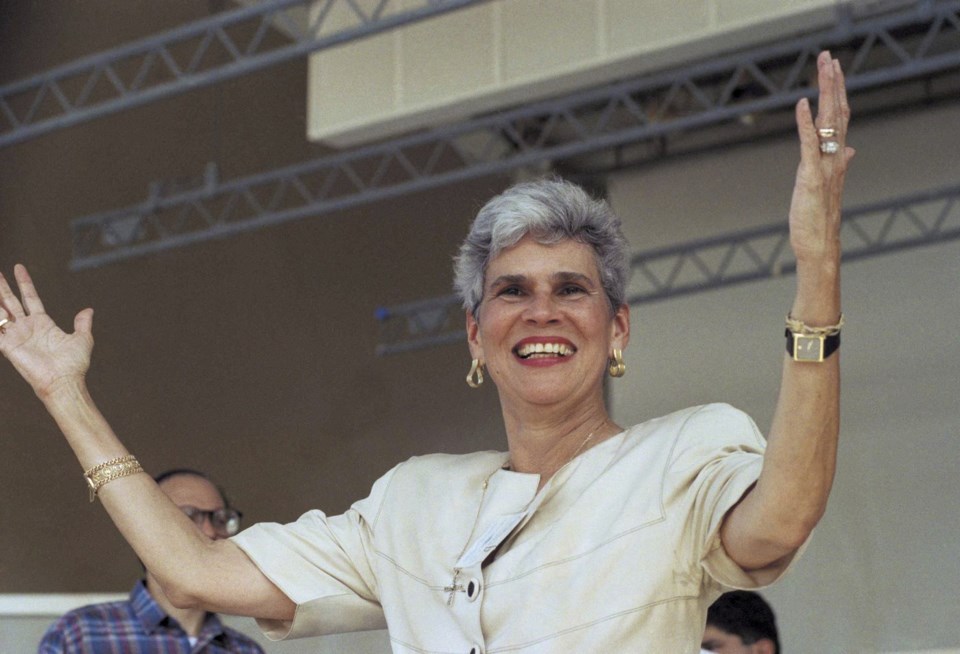

But elegant, silver-haired and dressed almost exclusively in white, she connected with many Nicaraguans tired of war and hardship. Her maternal image, coupled with promises of reconciliation and an end to the military draft, contrasted with OrtegaвҖҷs swagger and revolutionary rhetoric.

вҖңI bring the flag of love,вҖқ she told a rally shortly before the vote. вҖңHatred has only brought us war and hunger. With love will come peace and progress.вҖқ

She shocked the Sandinistas and the world by handily winning the election, hailing her victory as the fulfillment of her late husbandвҖҷs vision.

вҖңWe knew that in a free election we would achieve a democratic republic of the kind Pedro Joaquin always dreamed,вҖқ Chamorro said.

Washington lifted trade sanctions and promised aid to rebuild the nationвҖҷs ravaged economy, and by June the 19,000-strong Contra army had been disbanded, formally ending an eight-year war.

Forced into negotiations

Chamorro had little else to celebrate during her first months in office.

In the two months between the election and her inauguration, the Sandinistas looted the government, signing over government vehicles and houses to militants in a giveaway that became popularly known as вҖңthe pinata.вҖқ

Her plans to stabilize the hyperinflation-wracked economy with free-market reforms were met with stiff opposition from the Sandinistas, who had the loyalty of most of the countryвҖҷs organized labor.

ChamorroвҖҷs first 100 days in power were marred by two general strikes, the second of which led to street battles between protesters and government supporters. To restore order Chamorro called on the Sandinista-dominated army, testing the loyalty of the force led by Gen. Humberto Ortega, Daniel OrtegaвҖҷs older brother. The army took to the streets but did not act against the strikers.

Chamorro was forced into negotiations, broadening the growing rift between moderates and hardliners in her government. Eventually her vice president, Virgilio Godoy, became one over her most vocal critics.

Nicaraguans hoping that ChamorroвҖҷs election would quickly bring stability and economic progress were disappointed. Within a year some former Contras had taken up arms again, saying they were being persecuted by security forces still largely controlled by the Sandinistas. Few investors were willing to gamble on a destitute country with a volatile workforce, while foreign volunteers who had been willing to pick coffee and cotton in support of the Sandinistas had long departed.

вҖңWhat more do you want than to have the war ended?вҖқ Chamorro said after a year in office.

Vision of forgiveness

Chamorro was unable to undo NicaraguaвҖҷs dire poverty. By the end of her administration in early 1997, unemployment was measured at over 50 percent, while crime, drug abuse and prostitution вҖ” practically unheard of during the Sandinista years вҖ” soared.

That year she handed the presidential sash to another elected civilian: conservative Arnoldo Aleman, who also defeated Ortega at the ballot.

In her final months in office, Chamorro published an autobiography, вҖңDreams of the Heart,вҖқ in which she emphasized her vision of forgiveness and reconciliation.

вҖңAfter six years as president, she has broadened her definition of вҖҳmy childrenвҖҷ to include all Nicaraguans,вҖқ wrote a reviewer for the Los Angeles Times. вҖңSo even political opponents like Ortega are briefly criticized in one sentence, only to be generously forgiven in the next.вҖқ

After leaving office, Chamorro retired to her Managua home and her grandchildren. She generally steered clear of politics and created the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation.

In 2011 it was revealed that she suffered from a brain tumor. In October 2018, she was hospitalized and said by family members to be in вҖңdelicate conditionвҖқ after suffering a cerebral embolism, a kind of stroke.

The Associated Press