Chloe Dalton was taking a winter walk near her farmhouse when she encountered it: a tiny baby hare — known as a leveret — lying huddled and alone in the middle of a narrow country lane.

A London political adviser who was living in the English countryside during the pandemic, Dalton knew next to nothing about hares. Yet when she found that the leveret hadn't moved for hours, she decided to take it home and try to save it — despite her fears that by interfering she might hurt its ability to return to the wild.

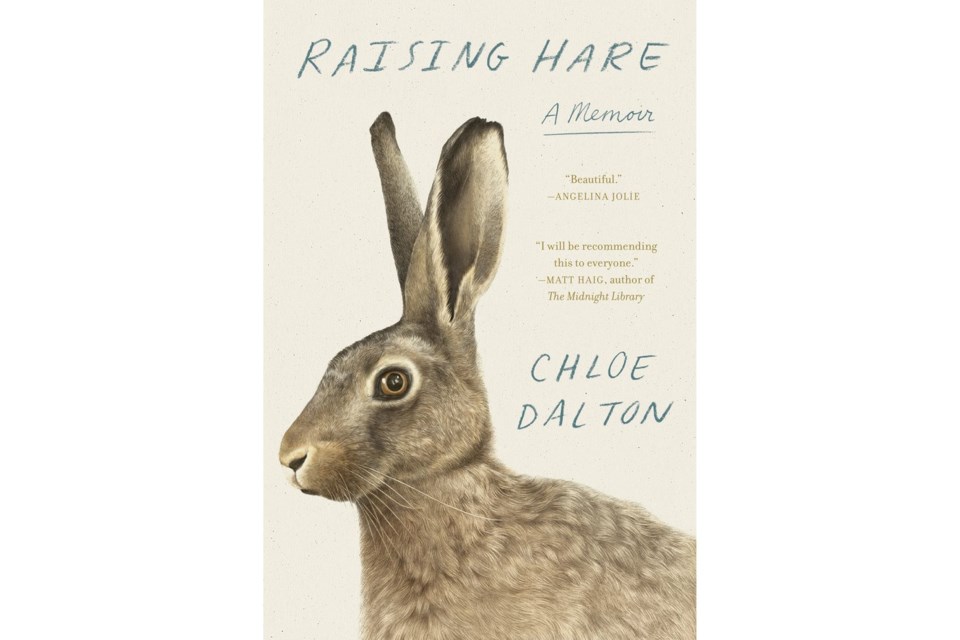

What follows, as recounted in the new memoir, “Raising Hare,” was an unexpected experiment in coexistence.

The book is part of a timely genre: true stories about people who open a window into the natural world through intense observation of one wild animal or species, often in their own backyard.

Think of Catherine Raven’s “Fox & I”; Sy Montgomery’s “Of Time and Turtles”; Helen Macdonald’s “H is for Hawk”; David Gessner’s new “The Book of Flaco”; Elisabeth Tova Bailey’s “The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating.”

Unexpected connections with other species can feel comforting and important at a time when wildlife is so besieged. Nature feels very far away — yet here it is in your backyard. And maybe, these stories say, you can do something to help.

It’s fascinating to learn along with Dalton as she looks for information about hares. She searches in books but finds little that's helpful. She’s led to believe, for instance, that the leveret will remain aloof; instead, it comes to feel comfortable, jumping around with her and curling up against her while it sleeps. Yet it also leaves for long stretches beyond her garden wall, returning on its own inscrutable timetable.

Dalton has to trust her instincts. Insisting that the animal isn't a pet, she doesn't name it, calling it just “little one.” She gives it free reign of her house and garden, making no demands and taking care never to startle it.

She describes the leveret's evolving behavior and body in painterly detail.

Her research into hares mostly reveals a history of sport and slaughter. Dalton notes their population's precipitous decline in England because of encroachment on their habitat (agriculture and its careless machines are particularly to blame.)

She notes changes in herself, too, as she adapts to a slower, simpler life. She begins to pay more attention to her wider natural surroundings. She notices predators, and watches the other hares beyond her wall.

“Raising Hare” is a plea for people to be gentler with other creatures, to grant them room to live.

“Coexistence,” she writes, “gives our own existence greater poignancy, and perhaps even grandeur.”

___

More AP book reviews:

Julia Rubin, The Associated Press