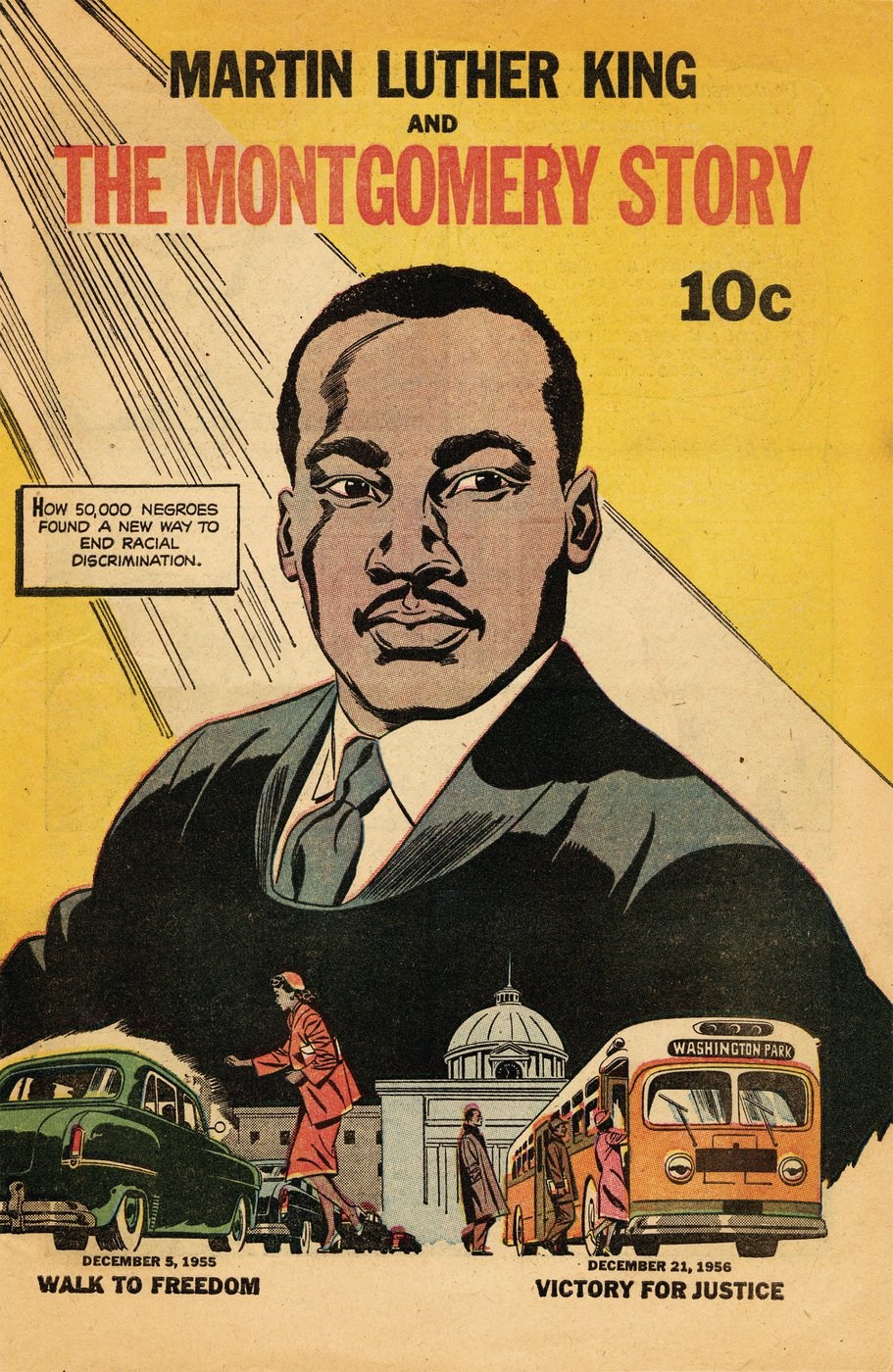

(RNS) ā At cross-cultural gatherings in Bethlehem, West Bank, groups of children and adults turn to a 67-year-old, with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.ās image on its cover, his tie and shirt collar visible beneath his clerical robe.

As they read from āMartin Luther King and the Montgomery Story,ā the group leader is prepared to discuss questions about achieving peace through nonviolent behavior.

āWhat are the teachings we have from Martin Luther King?ā asks Zoughbi Zoughbi, a Palestinian Christian who is the international president of the Fellowship of Reconciliation and founder of Wiāam: The Palestinian Conflict Transformation Center.

āHow can we benefit from it, and how do we deal with issues like that in the Palestinian area under the Israeli occupation? How to send a message of love, agape with assertiveness, not aggressive?ā

___

This content is written and produced by Religion News Service and distributed by The Associated Press. RNS and AP partner on some religion news content. RNS is solely responsible for this story.

___

Zoughbi told RNS in a phone interview that the comic book, published in 1958, remains a staple in his work, which includes both English and Arabic versions. (It is available in six languages.)

Over the decades, it was used in Arabic in the anti-government Arab Spring uprisings, in English in anti-apartheid activism in South Africa and in Spanish in Latin American ecclesial base communities, or small Catholic groups that meet for social justice activities and Bible study.

It continues to be a teaching tool and an influential historical account in the United States as well.

The book was distributed in January at New Yorkās Riverside Church and has been listed as a curriculum resource for Muslim schools. And it remains a popular item, available online and in print for $2, at the bookstore at Atlantaās Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. Store director Patricia Sampson called it āone of our best sellers.ā

The 16-page book was created by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a Christian-turned-interfaith anti-war organization. It was written by Alfred Hassler, then FOR-USAās executive secretary, in collaboration with the comic industryās Benton Resnik. A gift of $5,000 from the Ford Foundationās Fund for the Republic, a nonprofit advocating for free speech and religious liberty, helped support it.

āWe are a pacifist organization, and we believe deeply in the transformative power of nonviolence,ā said Ariel Gold, executive director of FOR-USA, based in Stony Point, New York. āAnd where this comic really fits into that is that we know that nonviolence is more than a catchphrase, and itās really something that comes out of a deep philosophy of love and an intensive strategy for political change.ā

The comic book bears out that philosophy, in part by telling the story of Kingās time in Montgomery, Alabama, where he was chosen to lead the Montgomery Improvement Association as Black riders of the cityās buses strove to no longer have to move to let white people sit down.

Their nonviolent actions, catalyzed by Rosa Parksā refusing to give up her seat in 1955, eventually led to a Supreme Court decision that segregated public busing was unconstitutional.

The comic book ends with a breakdown of āhow the Montgomery method works,ā with tips for how to foster nonviolence that include ādecide what special thing you are going to work onā and āsee your enemy as a human being ā¦ a child of God.ā

Ahead of publishing, Hassler received āadulation and a few correctionsā from King, to whom he sent a draft, said Andrew Aydin, who wrote his masterās thesis on the comic book and titled it āThe Comic Book that Changed the World.ā

The name of the comic bookās artist, long unknown, was revealed in 2018 to be Sy Barry, known for his artwork in āThe Phantomā comic strip, by the blog comicsbeat.com.

In an edition of FORās Fellowship magazine, King wrote in a letter about his appreciation for the comic book: āYou have done a marvelous job of grasping the underlying truth and philosophy of the movement.ā

The book quickly gained traction. The Jan. 1, 1958, edition of Fellowship noted the organization had received advance orders for 75,000 copies from local FOR groups, the National Council of Churches and the NAACP. An ad on its back page noted single copies cost 10 cents, and 5,000 could be ordered for $250.

By 2018, the magazine said some 250,000 copies had been distributed, āespecially throughout the Deep South.ā

The comic book has led to other series in the same genre that also seek to highlight civil rights efforts, using vivid images that synopsize historical accounts of the 1960s.

āMarch,ā a popular graphic novel trilogy (2013-2016), was created by U.S. Rep. John Lewis, along with Aydin, his then-congressional staffer, and artist Nate Powell, about Lewisā work in the Civil Rights Movement. A follow-up volume, āRun,ā was published in 2021.

āIt was part of learning the way of peace, the way of love, of nonviolence. Reading the Martin Luther King story, that little comic book, set me on the path that Iām on today,ā said Lewis, quoted in the online curriculum guide on FORās website.

More recently, a new grant-funded webcomic series, āBad Catholics, Good Trouble,ā was inspired by both the King comic book and āMarch,ā said creator Matthew Cressler.

Described as a āseries about antiracism and struggles for justice across American Catholic history,ā it chronicles the stories of Sister Angelica Schultz, a white Catholic nun who sought to improve housing access for African American residents in Chicago, and retired judge Arthur McFarland, who as a teenager worked to desegregate his Catholic high school in Charleston, South Carolina, and later encouraged the hiring of Black staff at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Cressler said the King comic bookās continued distribution and use in diverse educational settings āmake it one of the most significant comics in the history of comics ā which is something that might seem wild to say, given how when most people think about comic books, they think of superheroes like Superman or Batman.ā

Though different in topic and artistic style, Cressler said, the MLK comic book can be compared to āMausā by Art Spiegelman and āOn Tyrannyā by Timothy Snyder ā more recent graphic novels about a Jewish Holocaust survivor and threats to democracy, respectively ā āas a medium through which to teach, to educate and specifically to politically mobilize.ā

Anthony Nicotera, director of advancement for FOR-USA and an assistant professor at Seton Hall University, a Catholic school in South Orange, New Jersey, uses the King comic book in his peace and justice studies classes.

āPeople are using it in small ways or local ways or maybe even in larger ways,ā he said, āand we donāt find out until after itās happened.ā

Gold, a progressive Jew who is the first non-Christian to lead FOR-USA, said future versions are planned beyond the six current languages to further share the message of King, the boycott and nonviolence. She said this year, her organization is aiming to translate it into French and Hebrew, for use in joint Israeli-Palestinian studies and trainings on nonviolence, as well as for Jewish religious schools.

āEspecially in this political moment, I think we really need sources of hope, and we need reminders of the work and the strategy and the sacrifice that is required to successfully meet such an intense moment as this,ā she said.

Adelle M. Banks, The Associated Press